1275 Minnesota St /

re.riddle (Room 204)

Guest gallery re.riddle presents a solo exhibition of new work by Cheryl Derricotte.

When the prevailing narrative of history’s forgotten protagonists is conveyed through both folklore and fact, the question arises: who decides what is retold? Reclaiming the narrative subverts the inequities of power that dictate truth, becoming an existential act of rebellion— particularly for those whose moral compass was, simply put, ahead of their time. Friend of John, a solo exhibition of new work by artist Cheryl Derricotte, traces the porous, mythic history of Mary Ellen Pleasant (1814–1904), the abolitionist, “Mother of Civil Rights” in California and the first Black woman millionaire, by mapping her journey north from Nantucket to New Orleans through anthropological and visual storytelling.

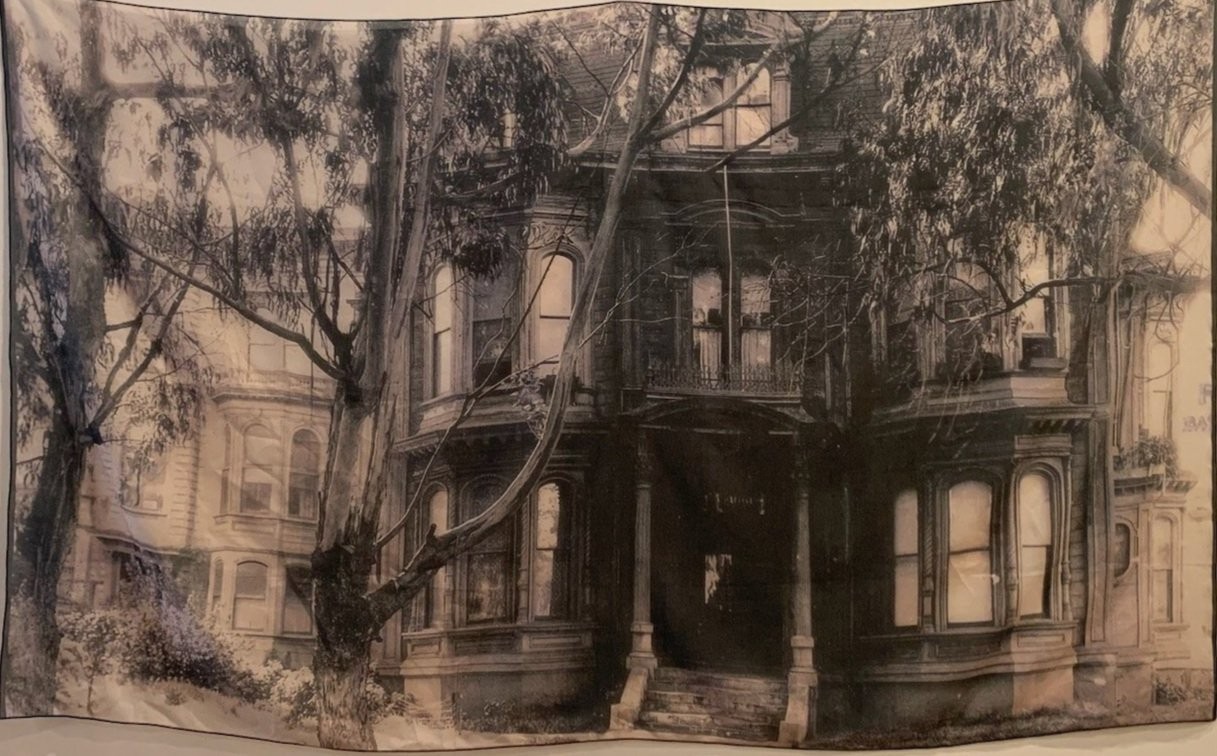

Friend of John is a double entendre and a play on words; it refers first and foremost to Mary Ellen Pleasant’s unwavering support of the abolitionist John Brown, and to her tombstone inscription “A Friend of John Brown,” a poetic final act of civil resistance. For this exhibition, Derricotte has combined historical research and archival images with contemporary photos of places connected to Mary Ellen Pleasant’s life in New Orleans. The resulting body of work comprises portraits and imagery on glass, works on paper, and a mixed media installation that reframe Pleasant’s influence, while critiquing the connections between place, community and power that she deftly navigated by subverting her own status.

Despite her wealth, upon arriving in California Pleasant lived much of her life as a cook and domestic servant for San Francisco’s elite. These relationships, including a long-term business partnership with Scottish financier and Bank of California Board Member Thomas Bell, ultimately enriched Pleasant by giving her access to the investment strategies of the white upper class, shared only behind closed doors. She shrewdly leveraged this insider knowledge to grow her own fortune and, by extension, to continue to support the Underground Railroad and provide critical services to freed and escaped slaves.

Pleasant transcended social constructs by adopting an identity that enabled her to infiltrate echelons of power, avoid detection and advance her political agenda. Due to the semi-clandestine nature of her web of capitalist enterprises and her simultaneous involvement with the freedom movement, Pleasant’s biography remains somewhat shrouded in mystery. As a means of survival, such anonymity was a necessary obfuscation of her influence during her lifetime, but, today, serves only to undermine her vast contributions to the abolitionist cause. By weaving together the tenuous threads of such visible—and invisible—spirits of resistance, resilience and liberation, Derricotte provides a timely resurrection of Pleasant as the shadowy saint of the abolitionist movement, whose mythic legacy offers both hope and inspiration for the activists of today.