1275 Minnesota St /

Nancy Toomey Fine Art

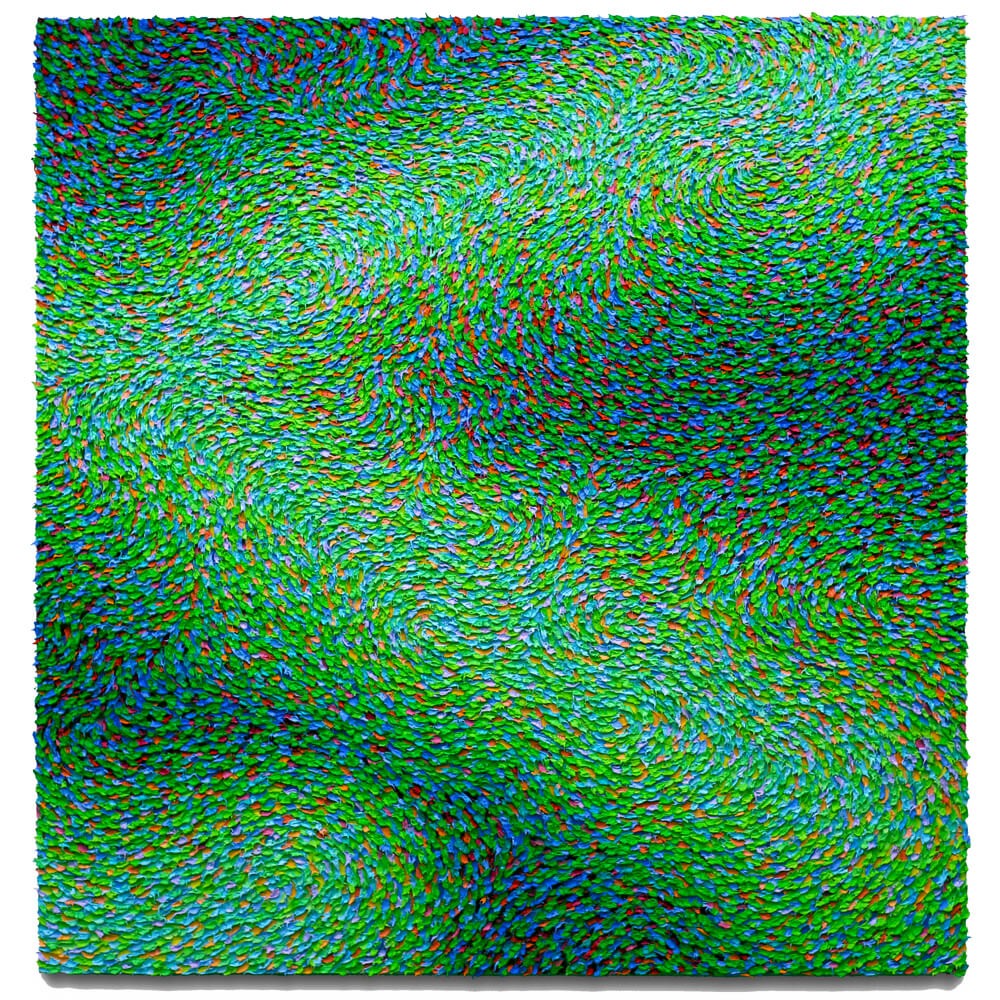

The relationship between abstract painting and the idea of the transcendent in Robert Sagerman's Numinous Substance exhibition has been at the core of his art practice for decades now, although his understanding of and approach to both have shifted considerably over time. From Sagerman's first forays into abstraction as an emerging artist, he had felt that there was a particular subject matter toward which his efforts were directed, that being the apprehension of the metaphysical. By this, he referred to the notion of an imperceptible immateriality underlying physical reality. Something about both the practice of painting abstractly and the visuality itself of field painting seemed to reference this nevertheless ultimately inaccessible transcendence. The sense that the full apprehension of this metaphysic was an impossibility was accompanied by the tantalizing intuition that there was nevertheless a fruitful path there to be pursued. It was this tension that led him to push his painting process to ever greater extremes, where mark upon mark would come to accumulate for months on end in a single piece, with a growing emphasis upon the sensuality of color and the physicality of mark-making.

Much later, as a graduate student, Sagerman learned that an analogous tendency was often operative in the realm of mystical practice, where those so engaged would frequently find recourse to highly sensual, even erotic, descriptions of their efforts, as their mystical experiences themselves would often also partake of these same qualities. Feeling an affinity with medieval mystical practice, he pursued the academic study of Jewish mysticism, earning a PhD along the way. What drew him to the practices and thought of Jewish mystics in particular was their impassioned effort to elaborate a dizzying system by which to conceptually and experientially bridge the gap between the transcendent, or divine, and the terrestrial world. He found that a full immersion in the effort to fathom this system was an effective tool for focussing his efforts in the studio along what seemed to him to be remarkably similar lines. The great stress laid by Jewish mystics (Kabbalists) upon the bringing forth of hidden meanings and symbolic motifs out of scripture was compelling for him, as it came to feel more and more that his studio practice was very much oriented toward pulling forth fresh meaning from what always struck him as a puzzling, even absurd, way of working. Often Kabbalistic motifs would resonate for the artist, but just as often the practice of inquiry itself seemed to be something he held in common with these practitioners.

Despite what Sagerman sees as his initial impetus toward the study of mysticism — the effort toward metaphysical apprehension — over time he has come to recognize that the theme of non-arrival, of the ultimately inescapable alterity of the transcendent, is something that is fully embraced in many Jewish mystical texts. To take but one notable example, medieval Kabbalists referred to the highest-most realm of the divine as the "Ehn Sof" in Hebrew, literally the "Without Limit." They emphasized its endlessness and the fact that it may only be encountered indirectly, in terms of what it is not. That is, one can say of it only, for instance, that it lacks any limit. By analogy once again, Sagerman's studio practice today more and more seems to embody a similar sense of non-arrival, of continuity and flux without the fixation upon an achievable destination. Because his sense of a reachable objective has become ever more clouded over time, his practice more than ever feels to have taken a non-referential turn.

"Today my painting practice presses forward with what I think of as different lineages of work that extend back in time for many years and proceed onward into indeterminacy," says Sagerman. "In terms of color modalities, composition, method of paint application, material usage or, sometimes, recourse to imagery, each painting today perpetuates prior ways of working. In some cases, prior threads intersect and merge within a given piece. So, for instance, pieces with color gradations often now have compositions of swirling, undulating marks, or pieces executed in silicone and pigment that were once always monochromatic now consist of color gradations. Sometimes modalities that had been set aside for years reemerge, as in the case of multicolor works composed simply of horizontal marks. As these different ways of working are combined and recombined, notably new threads arise. For instance, 21,629 from this exhibition contains a kind of organic, even off-kilter tonal gradation that I had worked with in a much more monochromatic way before, but which now is so polychromatic as to feel like the beginning of an entirely new vein of work. Similarly, the mandala-like symmetrical patterning of 8,689, combined with a color gradation, feels like something very new for me. These kinds of iterations seem inexhaustibly fertile, products of a work practice that feels eminently 'without limit.'"