"Mistakes" Make the Piece in Concrete Is Not Always Hard

by Laura Jaye Cramer

In the past ten years, San Francisco's Dogpatch has gone from being a sleepy little industrial corner, to one of the most happening neighborhoods in the city. And with spots like the American Industrial Center, Workshop, and the Museum of Craft and Design, it's established itself as a vibrant arts community as well.

Next to join in is the Minnesota Street Project, a new venue for up-and-coming artists. Once completed, (which should happen roughly around March of next year) the permanent space will boast 35,000 square feet of what founders Deborah and Andy Rappaport promise to be affordable retail, gallery, and studio space for creative professionals. It's a lofty idea — and if they can pull it off, they might just be the next heroes of the San Francisco art scene. Until then, Minnesota Street Projects will host exhibitions at temporary locations around the city. Their first was a stone's throw away from the construction sight of their future Minnesota location at a small gallery at 2291 Third Street. This inaugural show, Concrete Is Not Always Hard, was a solo show of dozens of ink on paper pieces by artistAjit Chauhan.

Chauhan, whose work has been seen in top museums and galleries worldwide (including the de Young and Asian Art Museums), created Concrete Is Not Always Hard around concepts presented by poet A. Barbara Pilon. In an essay from the 1970s, Pilon wrote, "Have you ever thought of writing a poem using only a letter, a word, distortions of words, nonsense words, or no words at all? Have you ever thought of using the space around words to help the reader understand the idea you are trying to communicate?"

And this description of wordless poems describes Concrete Is Not Always Hard to a T.

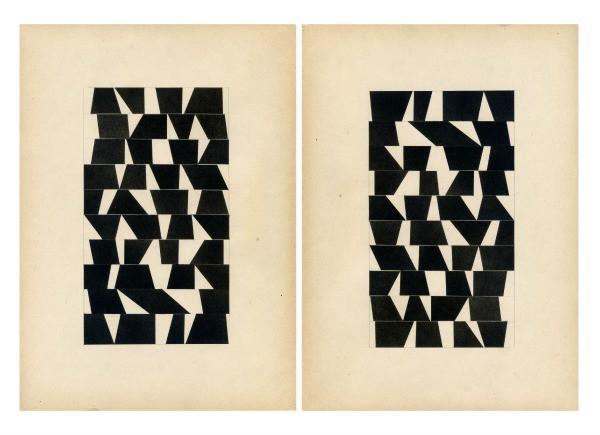

While some of Chauhan's pieces use dark geometric shapes to create pleasant-enough but more or less predictable patterns, his best works are made up of layered typewriter lettering. And like Pilon indicates, the letters are not used to create words. Instead, they're bunched together like a honeycombs to make shapes. But even in these lively packs, on their own each letter can be boiled down to a simple, delicate outline - a detail that is still conveyed even in the busiest of Chauhan's work.

In fact, his pieces are so delicate, it's hard not to imagine that they'd be swallowed up in an exhibition space the size of the future Minnesota Street Project. But in an intimate gallery like the one at 2291 Third, they seem right at home.

Which isn't to say that the art can't hold its own. Each is modest in size, and as a result, the viewer really has to lean into each piece. When combined with the vertiginous effects of the seemingly living patterns, suddenly these very small, mild works pack more of a punch then you might be inclined to give them on first glance.

It's the way that the letters are layered that seems to be key. Each pattern is completely different from the others; some with more negative space look like they could be some sort of futuristic lace, while a couple with more tightly woven letters could be altered photographs of chainmail. (And it's fun to imagine that others still contain secret messages. My Greek date noted in one piece that a succession of sideways "C's" could be read like a Greek "S", which, funnily enough, would make the secret message of that particular piece "Shhh!")

In one of the best in show, there were a few rogue letters throwing off the generally orderly composition. When briefly chatting with the Chauhan, he laughed the letters off. They are accidents, he explained, because the keys are close together — and, incidentally, they're the most interesting parts of the Concrete Is Not Always Hard. Where some have random letters, others have bits of tape sticking to their faces. As a result, the pieces lose any sort of neurotic stigma that sometimes hangs over repetitive creations. Instead, they seem good-natured and therapeutic — it's almost like the artwork exists as much for the artists' benefit as it is for the audience. And in a market where the appeal of trends so often trumps innovation, seeing someone create work simply because they want to be creating that work is terribly refreshing.